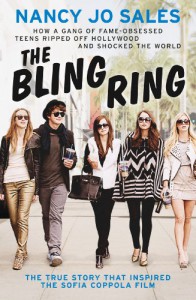

Currently reading

The Bling Ring: How a Gang of Fame-Obsessed Teens Ripped Off Hollywood and Shocked the World by Nancy Jo Sales

In the late 2000s, the entertainment media sphere was rocked by the story of ‘The Bling Ring’, a gang of rich Californian teens who would burglarise the homes of the rich and the famous, using modern day technology to assist them. This gang of privileged, troubled teens managed to steal from celebrities such as Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, Audrina Partridge, Orlando Bloom and Rachel Bilson whilst living the high life in the Californian valleys.

As the investigation progressed, it was discovered that the Bling Ring were only partially motivated by the monetary value of the items they stole. They would flaunt the celebrities’ clothing and jewellery whilst out and about, and even brag about their loot on social media websites. They were seemingly more interested in owning a ‘piece’ of the celebrities they admired. The celebrities who were famous for not much at all. Whereas old Hollywood celebrities had proven themselves in the rings of acting (Judy Garland), music (Frank Sinatra), dance (Fred Astaire), and other kinds of performance media, the new celebrities were simply famous for being in glitzy reality shows.

Nancy Jo Sales was among the first people to run an article about this odd criminal gang, in Vanity Fair. This book is an extension of that article, pulled out to over 250 pages to accompany the upcoming Sofia Coppola film. Many of Sofia Coppola’s films focus on the vacuity of fame, from Lost in Translation to Marie Antoinette, and now The Bling Ring. As Sales notes in the first part of this book, this was a perfect project for Coppola.

Unfortunately, the article being extended into a book is where it falls rather flat. Sales really has to reach for the stars in order to get some of its points to connect with each other. The author also has a habit of using pop culture references where they don’t really belong, such as comparing the teenagers opening Paris Hilton’s walk-in closet as ‘that scene where the dwarves discover the dragon’s treasure-laden lair in The Hobbit.’ It sounds apt, but really doesn’t fit. Orlando Bloom supposedly lives in a forested, ranch-style home that resembles ‘a Bat Cave.’ You mean the Bat Cave, I’m presuming? Oh, and let’s not forget Sales ludicrously comparing the fame bubble to ‘the force field thrown out by Violet, the “super” girl from The Incredibles.’

There’s also a lot of stupidly obvious observations, wherein Sales repeats herself as if talking to complete plebeians. I mean, I may not work for a prestigious magazine like Vanity Fair, but I’m quite sure I can glean what Lady Gaga is trying to say in her song ‘Paparazzi’ (page 17), or that Disney’sHigh School Musical movies are about ‘high school kids vying for roles in a high school musical.’ (Page 29.) This whole part about High School Musical doesn’t really make sense, as the previous paragraph builds up the idea that throughout the 2000s, there were many American movies and TV shows which showed how one could be rewarded with instant notoriety simply by showing off a certain skill, or even by just making an arse of yourself on camera. High School Musical isn’t really centred around fame, though. The plot revolves around exactly what it says on the label, a high school musical. It’s got nothing to do with the fame analogy, except for perhaps the character Sharpay (portrayed by Ashley Tisdale) clearly being written with Paris Hilton in mind. (Yes, I’ve watched those movies. Shush.)

Shortly after this, Sales even tries to divine meaning out of the lyrics of the theme song to the Disney sitcom Hannah Montana, which, granted, does revolve around being a famous pop idol, with Miley Cyrus as the face of a huge tween merchandising empire. I’d be fine with Sales explaining the premise of Hannah Montana, and relating its enormous popularity to the cultural obsession with overnight fame, but the lyrics of the theme song simply do not back up the point she is trying to make.

The main problem with Sales’ writing is that she trundles along with the points she is trying to make, using anecdotes and some research taken from sociological, anthropological and psychological studies. Then, she plops this one interesting point right at the end of the paragraph, like “Ta-da! There it is. Anyway, moving on!”

While Sales does have a salient point in that Western culture did become obsessed with the reality show (and still is, to some extent), she too often goes off on complete tangents. Demi Lovato was once quoted as saying that X Factor contestants are put into luxury hotels to give them a taste of the celebrity lifestyle. Sales follows that up with a completely irrelevant sentence about how Lovato and her co-judge, Britney Spears, were also in rehab, which is part of the ‘celebrity lifestyle.’ Right…

Sales also has a problem with making some very sweeping generalisations. The subjects up for debate are the rise in narcissism, the rate at which boys leave education or are diagnosed with ADHD, the fracturing of the family unit, female conditioning, teenagers over time, and even hip-hop music. Apparently, even a little girl in a Disney princess ball gown and a plastic tiara is a narcissist in the same vein as Paris Hilton or one of the Kardashian sisters, as are the parents who buy those jokey ‘I’m Spoiled Rotten’ or ‘I’m A Little Princess’ shirts for infants. Parents who fed into their children’s egos by being less strict than their own ‘Depression-era’ parents are blamed for causing ‘Failure to Launch’ syndrome, in which young adults don’t feel they are able to live independently of their parents. Pfft, the lousy economy, high rate of student debt and unemployment doesn’t exist, what are you talking about?

Let’s not forget that teenagers have shaped the United States throughout its history, as Sales reminds us that ‘sixteen of the 116 known participants at the Boston Tea Party were teenagers.’ My gosh, woman, slow down, that’s almost fourteen per cent! Plus, the concept of the ‘teenager‘ wasn’t thought up until the 1950s. Back then, they were just ‘young people.’

Oh, how about hip-hop? It’s fairly ignorant for Sales to say that hip-hop music was once a method of communicating social and political inequalities, and is now all about wealth and ‘gangsterism’, as if politically-charged hip hop was completely swallowed up by the gangsta rap of Jay Z, 50 Cent and P. Diddy, and doesn’t exist any more. But Sales does just that, after telling us about how two of the perps would drive around these moneyed areas of California listening to club hits by Lil Wayne.

Our writer also harks back to the days of Old Hollywood, before shows like Dynasty and Dallas offered a dramatic look into the modern world of the super rich. On page 72, Sales wonders why the people living in Hollywood aren’t constantly being burgled, since ‘ironically, the movies specialise in glamourising thieves.’ She gives three examples: The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), The Italian Job(1969), and How to Steal a Million (1966). All three films come from a different time in Hollywood, and with the point Sales is trying to make about modern reality, you wonder why she didn’t go for the remake of The Italian Job, or even the Ocean’s Eleven movies.

However, looking aside from all the inconsistencies, generalisations, arguments and points which don’t hold much water, stupidly obvious observations and baffling pop culture references, does Sales manage to tell the story of this brat pack, how they lived the high life, and how the perpetrators eventually got too cocky and were caught out?

Yes. Yes she does. The Bling Ring is hardly a bad read, and with the use of Sales’ anecdotes and some research sketchily tossed into the bag, The Bling Ring did achieve its goal of presenting a readable account of Hollywood’s most famous ring of teenage burglars, perfectly in time for the movie, and also in time for the summer, I suppose, if the book shelf at my local supermarket is to be believed.

Sales thankfully ceases using so many pop culture references, generalisations and points that would perhaps be salient if she developed them a little bit more rather than just throwing out the reference. When the book finally gets into gear and stops relating fame to some kid playing with a Bratz doll and deciding to be a snotty little madam obsessed with the celebrity lifestyle, it’s a fairly compelling, if at times blathering account of an unusual criminal case.

The Bling Ring is not a badly-researched account. Sales is the journalistic authority on the case, having seriously done her work beforehand, and trying to score interviews with all the perpetrators and everybody even tangentially involved. However, even with a long bibliography at the end of the book, the way the references are written brings to mind somebody desperately grasping at straws. 2/5.